Next: The low Grashof number

Up: Spherical enclosures

Previous: Previous work

Contents

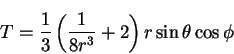

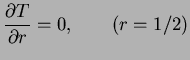

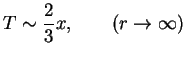

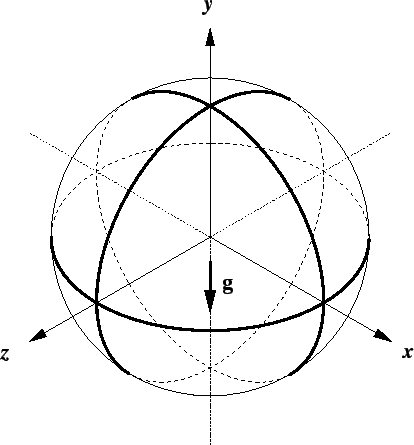

Take the diameter of the sphere as the length scale,  , and introduce

spherical polar coordinates relative to the positive

, and introduce

spherical polar coordinates relative to the positive  -axis:

-axis:

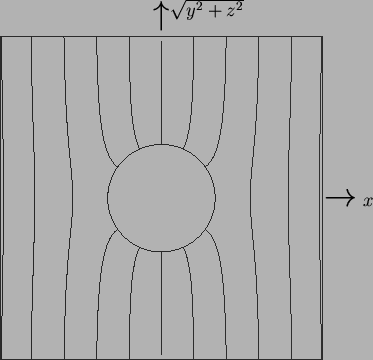

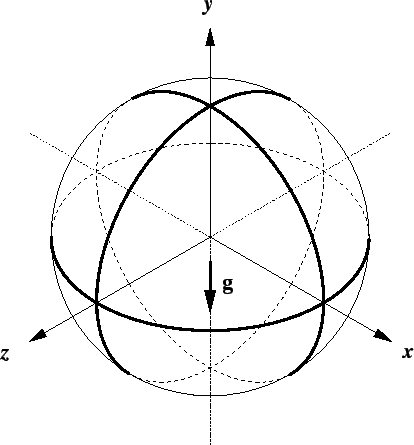

The relation of the Cartesian axes to the directions of gravity and the

imposed gradients, as illustrated in figure 8.1,

Figure 8.1:

Cartesian axes for the spherical cavity subjected to a linear

variation with  of vapour mass fraction and temperature at the boundary.

of vapour mass fraction and temperature at the boundary.

|

is the same as for the cuboid.

Ostroumov's (1958) study is more general than mine in that it considers the

finite conductivity of the surrounding solid. Since solids, in general,

are much

more conducting than gases, and since the primary purpose here is to illuminate

confined convective flow, let us assume that the solid is infinitely conducting.

If the temperature gradient in the solid far from the cavity is uniform and

horizontal (parallel to the  -axis), the temperature at the boundary

of the sphere is analogous to the flow potential on a solid sphere moving along

the

-axis), the temperature at the boundary

of the sphere is analogous to the flow potential on a solid sphere moving along

the  -axis through a perfect fluid; i.e. it varies linearly with

-axis through a perfect fluid; i.e. it varies linearly with  (Lamb

1932, p. 123), though the gradient differs from that in the far solid.

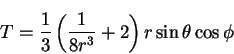

Explicitly, the temperature field

(Lamb

1932, p. 123), though the gradient differs from that in the far solid.

Explicitly, the temperature field

|

(8.5) |

satisfies

and leads to  on the boundary of the cavity. The temperature field

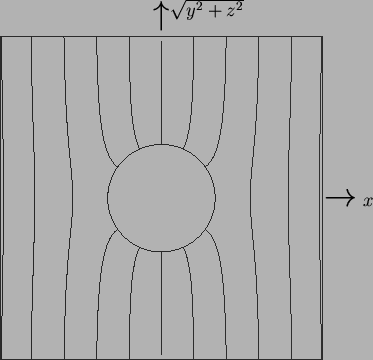

in the surrounding solid is shown in figure 8.2.

on the boundary of the cavity. The temperature field

in the surrounding solid is shown in figure 8.2.

Figure 8.2:

Temperature in the highly conducting solid surrounding a spherical cavity.

The field is axisymmetric everywhere, and linear in the far field.

|

This point appears to have been missed by Lewis (1950) and Ostrach (1988), who

thought that `this temperature corresponds to that which would occur in the

solid without gas bubbles' (Ostrach 1988),

which is true but irrelevant.

As in §7.5.2, it is assumed that the vapour mass fraction

at the boundary is a linear function of temperature; thus,

|

(8.9) |

Next: The low Grashof number

Up: Spherical enclosures

Previous: Previous work

Contents

Geordie McBain

2001-01-27

![]() , and introduce

spherical polar coordinates relative to the positive

, and introduce

spherical polar coordinates relative to the positive ![]() -axis:

-axis:

![]() -axis), the temperature at the boundary

of the sphere is analogous to the flow potential on a solid sphere moving along

the

-axis), the temperature at the boundary

of the sphere is analogous to the flow potential on a solid sphere moving along

the ![]() -axis through a perfect fluid; i.e. it varies linearly with

-axis through a perfect fluid; i.e. it varies linearly with ![]() (Lamb

1932, p. 123), though the gradient differs from that in the far solid.

Explicitly, the temperature field

(Lamb

1932, p. 123), though the gradient differs from that in the far solid.

Explicitly, the temperature field